Ford Carpenter’s 1903 photo-diary—Early exploration of Baja—Skirting the limits of Credulity–The trials of Pingree Osburn—Some near historical analogs—The stream between the meadows—The Enchanted Place—Don Rolando Arce—An extinct volcano—A missed opportunity—A long walk—Further meadow ecology—Another missed opportunity—Observations on the team

6 June, Camp, La Grulla, 6:30am

Last night was the coldest yet and James reported frost on the meadow in the early morning pre-dawn. We breakfast early and set off about 7:15am for La Encantada (the enchanted place)—a meadow larger even than La Grulla about 6 miles to the east. The idea is to bird along the way, and to locate some of Ford Carpenter’s photos from his 1903 expedition. Carpenter and his men trekked from San Felipe, on the coast of the Gulf of California (also known as the Sea of Cortez), across the Vizcaino Desert, up the eastern scarp of the Sierra San Pedro, and down the western slope, through La Encantada and La Grulla, San Telmo Valley, and to the Pacific. Carpenter was an aerial photographer and meteorologist from Southern California whose archive is in San Diego. His was the first photo-documented expedition in the Sierra, a photocopy of which we brought along because of its rich and interesting photographs of the meadows.

Thinking of walking through a place the Spanish described as “enchanted” recalls to mind that not very long ago, Americans had about as much familiarity with Baja as they might have had with Botswana. Carpenter’s expedition falls in the middle of a period of increasing interest in the region not only scientifically, but as a source of romantic natural history. The idea that just south of Los Angeles or San Diego lay an “uncharted” wilderness, “a place of wonderment and mystery” (NYT 8/13/1911) whose “human and animal inhabitants” have inspired more “strange tales” “than any other part of this Pacific Coast,” was especially exciting. “Almost every month of the year witnesses the return of some scientific expedition to Southern [Lower] California” from one Los Angeles area scientific institution or another (LAT 12/25/1926). To Hungarian explorer-naturalist John Xantus, writing in 1859, Baja might as well have been “terra incognita,” having “created in my mind an aura of fantasy” as “romantic” as anything conjured by Edgar Allen Poe’s 1838 Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, whose titular character stows away aboard a ship bound for Antarctica.

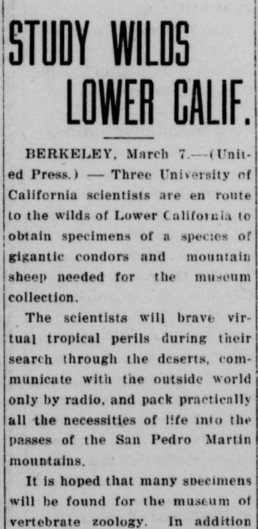

Universities and teams of museum scientists were keen to send agents down to this “little known region where the search may be rewarded with highly valuable finds,” such as “living gigantic condors and sheep,” “fossils of prehistoric monsters believed to have roamed the peninsula country” (Madera Tribune 3/7/1925), and the “fabled sea elephant” (NYT 8/13/1911)—“monsters of the deep about whose existence there had been serious doubt” (LAT 6/25/1911). The existence of such monsters may have been inspired by accounts of mythical beasts dating to the earliest Europeans to visit. Missionaries and explorers had been writing detailed natural histories of Baja since the 17th century, and while many of these accounts contain astonishingly accurate descriptions of flora and fauna, they also follow a tradition of European natural history dating to the ancient Roman armchair naturalist Pliny, whose own 2nd century Historia Naturalis contains some rather dubious entries. For example, the cynocephali or dog-headed men (later revealed most likely to be a baboon), and the anthropophagi or fearsome man-eating animals like the mantichora. Both were made famous by Shakesepeare’s Othello, who populates his traveler’s tales with such curiosities to woo beloved Desdemona, who serves as analog for a Europe beset with the fever-dreams inspired by first contact with non-European cultures (1.3).

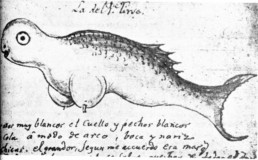

Among the records left behind by 18th-century Spanish missionary Miguel del Barco was a very Plinian characterization of a mountain sheep (probably Ovis canadensis mexicana) that, when pursued by Indian hunters, throws himself off a precipice, “taking care to land squarely on his head so that his thick horns can absorb the impact of the fall” (44). This same observer noted with Darwinian accuracy the aquatic behaviors of cormorants and the reproductive habits of a species of wasp that lays its eggs in mud cells, which it fills with spiders to feed hatching larva (97-98): “since the spiders are so well protected from the air they keep fresh for a long time” (97). Among the visual records of German Jesuit missionary Ignacio Tirsch was an illustration of a mermaid that looks suspiciously like an elephant seal, a monster Tirsch—had he in fact seen one—may have tried to explain through existing European mythology. From bestiaries to bigfoot, natural history has always skirted the limits of credulity, and I am reminded of something the late evolutionary biologist William Donald Hamilton once observed: “Naturalists are used to being disbelieved. Nature is so fantastic that it is true that we could, if we wanted to, get away with almost anything, and most people suppose that we do” (qtd. in Anderson, Deep Things 252).

Mythical beasts or no, Lower California was not without its dangers, which the press was eager to sensationalize. The threat of severe storms, the lack of roads and communication, extreme desert exposure, “semi-savages,” and lawless Mexicans all contributed to the romance of exploration and wilderness in a region that was just beginning to see the taming of its natural resources by the forces of development. One 1908 expedition found the young Pasadena man and one-time collaborator of Lamb’s, Pingree Osburn, in peril of his life. Sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History, Osburn was to lead a team of experts to the far south of Baja. They left April 21, 1911 aboard the Albatross bound for Cabo San Lucas, where Osburn was—like another Darwin—to trek inland and alone for a month to a place called Mira Flores, a remote mountain location isolated “by a wide desert” and known to be “infested with some rare animals and birds” that would make a fine collection (LAT 6/25/1911). Osburn was especially interested in a species of rare wild deer and an endemic black hare that lives in coastal caves of sea cliffs and mesas. However, in an experience the LA Times described as “a repetition of the adventures of Robinson Crusoe” (LAT 6/26/1911), Osburn failed to return with the Albatross: Accounts reached Los Angeles that the “intrepid scientist” had not only been “delayed and miscarried on account of the revolution” (LAT 6/7/1911), but that he lay very ill at Mira Flores with a mysterious ailment known only as “Mexican fever” (LAT 6/14/1911).

Osburn’s ailment turns out to have been–rathern unromantically–overwork and dehydration, but rumors had already spread that he “had been attacked by a dreadful southern fever, and that he had been taken prisoner by the insurrectos,” and finally that he had died, friendless and alone, in the wilds of Lower California (LAT 6/14/1911). Meanwhile, reports suggested his trip had been a success, and “a vast amount of invaluable material” had been collected. The “exact nature” of Osburn’s treasure was yet unclear: he’d had to leave it in care of a man he barely knew (LAT 6/25/1911) and it would “not be made known until his return” if ever (LAT 6/14/1911). Osburn lived to give his own account of his expedition to the LA Times. He reported collecting under the threat of mountain lions, bandits, and rabid coyotes before falling ill and finally being rescued by his brother. The story of this “youngest field collector” to the American Museum of Natural History made Osburn a local celebrity and it made for good copy: It was followed eagerly for weeks and confirms a growing public taste for natural history around this time.

As late as 1929, one of Carpenter’s contacts at the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, a Mr. Arnoll, saw business potential in the allure of an unexplored wilderness whose “conditions…today are exactly the same as they were when Cortez conquered Mexico.” Pristine wilderness has ever been a source of entrepreneurial speculation, and so Arnoll urged getting “some responsible parties…to organize tours by boat down into that region for hunting and fishing” in order to “work up a real interest.” Here was exotic nature in our own back yard: why “go to far away Africa to see primitive conditions that can be just as easily found within a few hundred miles of this city” (9/5/29)?

One natural history expedition organized by Pomona College in 1924 was truly interdisciplinary. This round trip of around 650 miles in “machines” (cars) packed with supplies and tents included scientists (a botanist, a geologist, an ornithologist, and an entomologist), a Spanish professor following the travel diary of Junipero Serra (who founded one of the first Franciscan missions in Baja), a photographer, and one Dr. Bruce McCully, head of the Pomona department of English literature, “who will be “looking out for material bearing on his own subject” (LA Times, 12/28/1924). I wonder what Dr. McCully’s subject was, and whether he spent any time fretting about it.

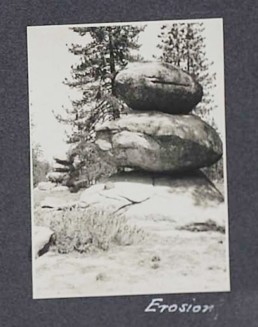

In addition to Carpenter’s, we also have a couple of photos from Lamb and Borell’s 1925 trip, including one of meeting a party of scientists led by Duncan Strong, an anthropologist who went on to write an account of Aboriginal Society in Southern California (1929), accompanied by a Mr. Hope and Mr and Mrs Schenk. It includes Lamb, standing in a somewhat revealing pose, awkwardly and to the left of the party, as if deferring to them, or maybe a little embarrassed (#4810). They pose next to a rough cabin, and in front of a distinctive rock formation in which one huge slab of granite oozes over another. At first glance the photo seems unremarkable, but in reality it contains a stratigraphic sampling of the uses to which the meadow has been put: One scientist photographs other scientists in front of an old rancher’s cabin. In any case the physical features seem so remarkable that we feel confident we’ll have no trouble locating them.

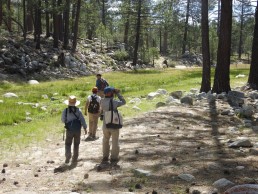

We’re in for a 14-mile round-trip walk today through the lengths of both La Grulla and La Encantada Meadows, along the stream running through La Grulla and which leads eastward. We’re following the Rio Santo Domingo watershed essentially to its source. Before we leave La Grulla we spy and snap a lone coyote making its way across the meadow, perhaps on the trail of a couple of mule deer we saw just ten minutes earlier. The coyote provides a helpful, if daunting, sense of the scale of this landscape.

The path skirts the north side of the meadow, leading into granite hills of pine, oaks, and a species of manzanita (Arctostaphylos—perhaps glauca, Big Berry Manzanita, but also greener). Rose sage and rock roses too line the walk. And cedars, tall and green and golden. Birds are quiet, but we note a Spotted Towhee, a striking, red-brown and black bird with a white breast and strings of pearl-white spots on its dark wings. The manzanita are frequented by Marine Blues (Leptotes marina) and a species of sulphur (genus Colias).

After leaving La Grulla it is a dry walk except where the trail crosses the stream and we’re forced to hop it at numerous points. John earns the nickname “Shetland pony” for a particularly accomplished leap despite his short stature–the same leap I, of the longer legs, fail to make so successfully.

The stream is narrow and mostly covered in some kind of stream “lettuce”, and low arroyo willows. Don Rolando leads the way on a white horse—looking the part of a real vaquero: leather chaps, jeans, and jean jacket with a wide brimmed hat. He sports a striking, white Spanish-style mustache. He waits for us at intervals, descending from his steed to nap in the grass until we, footsore and weary from hauling ourselves over the rocky landscape, catch up. It’s a guide’s life!

I discover on this walk that Don Rolando’s surname is Arce. Arce, I recall from Christian Meling’s book, is the name of the original grantees of the San Jose Ranch. In 1910 the Johnsons bought the ranch from Carmen Mandriguez, whose father was one Gabriel Arce (Sanford 41). Either he or, according to another source, a man called Ignacio de Jesus de Arce had been given the original grant in 1834. Ignacio (or maybe Gabriel) was himself a descendant of Juan de Arce, an Englishman who arrived at Loreto as a soldier in 1698. Juan de Arce was “one of the oldest settlers of the peninsula,” who acquired a Spanish surname after a while (Baja Legends 134).

It is easy to imagine that Rolando Arce may be related to the original title holder of the San Jose/Johnson/Meling Ranch. Don Rolando now ranches cattle at La Grulla, which means his family belongs to the ejido. If all this is accurate, then Rolando represents an interesting parallel to the layering of land-use histories and practices in these mountains: his family were the original European settlers who became grantees of the Mexican government in the nineteenth century; they sold their grant to another European family that eventually became one of the few private ranching outfits in the Sierra, Rancho Meling; meanwhile Rolando’s family was granted rights to the land through the land reforms of the Mexican Revolution—rights that were grandfathered in when the Parque Nacional was constituted in 1947. Politics, conservation science, and private property intersect in this region’s history, and in Rolando himself. There’s a certain irony in all this, made perhaps more vivid by the fact that Rolando makes his living partly on cattle ranching but also partly on running pack trips into the mountains for mostly American recreationalists and scientists—trips that are organized and paid for through Christian Meling, descendant of the family that bought the Arce land title.

6 June, La Encantada, 10:30am

When we first arrive in the meadow we’re on the make for some of Carpenter’s photos—in particular one of a distinctive mountain landscape that Carpenter called “An Extinct Volcano,” but is in reality an eroded granite mound. The meadow itself is probably an alluvial bed, the remains of Carpenter’s “volcano” and other surrounding metamorphic rocks, ground to silt and sand by ages of water run-off. Despite the similar geological origins, these mountains look nothing like the glacier-carved cathedrals of the Sierra Nevada.

We easily match the skyline to the photo, but locating the actual shooting location proves a lot more difficult. The rocks in the foreground of Carpenter’s photo never materialize for us, search as we might. And though we shoot the actual mountain, but from a closer vantage than the original. I think forest has reclaimed some of the meadow. Carpenter’s original may have been quite a distance behind our vantage, now obscured by trees. We have to satisfy ourselves that we did the best we could.

John and Whitney also locate the distinctive 3-tiered boulder formation that Carpenter mysteriously labeled “erosion.” It’s a huge granite snowman or giant cairn, with another nearly identical formation in the background. In our photo, the background cairn is obscured by pines. It’s a charismatic feature and a few of us pose with it.

Unfortunately, we completely miss our chance to shoot Borell’s photo of the La Encantada skyline (4778, “Meadow—La Encantada” 5/29/1925)—completely forgetting to break out the book at all. This would have been a real disapppointment, but there’s a silver lining. I accidentally did make the reshoot. My subjects were not the Borell photo at all, but James, his “adventure tote,” and Don Rolando on his horse—a particularly bucolic scene of them walking and talking along a cattle path in La Encantada with mountains on the right and pines on the left. Later, when reviewing Borell’s and Carpenter’s photos, I realize that Borell more or less reproduced Carpenter’s shot, and I’ve more or reproduced Borell’s shot. I doubt that Borell knew of Carpenter’s scrapbook, and so it’s more than likely the matchup was accidental. The fact that I shoot Borell’s by accident leads me to think about how such views are constructed for us. The three of us stopped to take the same photo for a reason. Maybe this view spoke to us all at some aesthetic level that none of us were aware of. Maybe the scale of the landscape struck us all in the same way, upon first entering the meadow from the forest. It makes me wonder if we take photos or if photos take us.

The landscape in all three photos is identical. Almost nothing has changed since 1903–that’s 115 years! Perhaps there are few fewer pines now on the right side of the mountain, and the grass was longer then. The fact that we can’t locate the rocks in the foreground of Carpenter’s “volcano” photo suggest maybe that the forest line has encroached somewhat on the meadow. This is consistent with what I know about forests and humans elsewhere in California and North America more generally: without humans, forests dominate. The High Sierra meadows that John Muir first encountered in California were likely the result of thousands of years of indigenous landscaping. When the California Indians were removed from those places, many of those “pristine” meadows reverted to forest (Anderson, ch. 5). Our inability to find those rocks could therefore be a small sign that meadow-grazing has fallen off somewhat over the last century.

Don Rolando thinks that perhaps the cabin in photo #4810 lay at the far northern end of the meadow. We realize this means experiencing the full effects of intense meadow exposure for another two or three hours. I’m not super excited about this. La Encantada is a sandy, hot, dry meadow, if possible sandier and hotter and drier La Grulla. The lush green carpets of La Grulla are here grazed down to sand. It is both longer and wider than La Grulla, and more intimidating: we walk and walk without seeming to make much progress; surrounding mountains don’t appear to advance or recede; no boulder islands provide helpful milestones or targets; and the pine forest we’re skirting provides little diversity to mark its passing.

Some of what makes for an unpleasant walk also reveals what is interesting and distinctive about these meadows and perhaps why they are so interesting to scientists. Grinnell noted—and we’re experiencing—the wide range of temperature fluctuation during the day: cool and damp in the morning, hot and dry in the afternoon, then plunging again in the evening. He speculated that intense sun exposure combined with the “daily fluctuation” of temperature, and accompanying “great dryness, must have its effect on the animal life, as it most certainly does on the plant life.”

As about a lot of other things, Grinnell was right about this. Unrelenting solar radiation and increasing aridity are determining features of this region. Northern Mexico’s geographic position means that that it is perpetually pummeled by solar radiation, daily and annually. Its geographic position hasn’t changed for almost 55 million years, or almost as long as the Cenozoic period, resulting in the historical “dominance of arid climates observed in the region” (Cartron 39). These geographic and climatic conditions have profoundly affected soil conditions as well as plants and animals (Cartron 26). Grinnell noted (as we’ve observed) that “The plants have noticeably small or narrower leaves than their congeners that I am familiar with in central California, even in the interior foot-hill country” (FN, 10.2.1925, p2559). Anything living and growing in the Sierra and the surrounding deserts has had to adapt to forbidding conditions. No wonder that the region has resisted human development, as well: as a relatively recent colonial species, we simply haven’t been able to make a niche for ourselves, despite the technologies we’ve marshaled in our service.

These “upland plateaus” or meadows have played an important part in this story, as well. They have allowed plants and animals from the north to establish footholds here by providing a continuous range of habitats along the mountains, like stepping stones. Along these high-elevation plateaus, the pine and pine-oak forests of the north can creep southward (Cartron 27). But at the same time, the geographic diversity in these mountains promotes “regional biotic differentiation,” or adaptations found here and nowhere else. In other words, as organisms migrated south, they had to adapt to region-specific conditions, which promoted unusual diversity and endemism.

Along the way, James and Devon distract themselves from the heat and tedium of this UV-exposed slog by fantasizing about their favorite fast foods. James and Dev have a real schtick going with this banter and it’s obvious that there’s a mild father/son relationship between the two: James constantly rides Devon and challenges him on birds and just about everything else. There’s a story they like to tell about perusing the Occidental College campus store, looking at Occidental-branded clothing with “Oxy Dad” printed on it. Devon’s initials are DAD (“Oxy DAD”) and a security guard overhearing them assumed that Devon was taking his father on a campus tour.

We note a couple species of Blue in the meadow grasss growing in the sandy-loamy soil along the way: Ceraunus Blue (Hemiargus ceraunus), a colorless spotted blue with a large, distinctive black eyespot on the underwing of the hindwing, usually accompanied by 1 or 2 small black spots, unlike the Marine Blue, which has just one; and the Acmon Blue (Icaricia acmon), with a band of 5 or so orange and black chevrons on the upper and underside of the hind wings.

6 June, La Encantada, 1pm

We arrive at the dilapidated “cabin” around and quickly discovered that it isn’t the cabin in our photo—no distinctive rocks nearby. It looks to be an old rancher’s waystation, now filled with a few plastic bottles and some old bedding, and smelling of piss.

After a short lunch John and I set out across the meadow to investigate another cabin we’ve spotted and another potential shot at the #4810 photo. No luck here either. This was another rephotography fail: had we checked the field notes that we bothered lugging along, we’d have realized that Lamb and Borell camped far to the north, where a stream feeds the meadow, and that there’s a cabin there, too. As with San Telmo, the photo was almost certainly taken directly from their camp.

The walk back is long and hungry. We have just one new bird to add to the list, the California Scrub Jay, a couple of “good enough” re-photographs, and some butterflies. By the time we reach our corner of La Grulla, the party is pretty well worn out. But we do manage to stop to re-shoot a couple more of Carpenter’s charismatic rock formations in La Grulla, just to the north of our camp.

In total we’ve walked 14-15 miles, but on the upside we are met with another of Aede’s delicious meals, a vegetable stew with zucchini, tomatoes, and onions, with rice and hand-made tortillas. Aeda is quiet but seems kind. The language barrier continues to nag at me: I often wish I can communicate with her without John’s help.

6 June, Camp, La Grulla, 8pm

By the campfire our conversation turns to family histories. John was born in Des Moines and grew up in Kansas City and eventually Phoenix. His father was an insurance man, his mother mostly an at-home mom. He has one brother, an accountant in Phoenix. John did his grad work at UCLA and a post-doc at Louisiana State (LSU), where many of Grinnell’s former protoges ended up—a much storied place in zoology. Back in LA he has a cool analytical demeanor, but I see a different side of him in the field: more demonstratively happy, almost goofy, in his enthusiasm for the work at hand. He’s very happy to share his knowledge. His field style is simple: khakis and t-shirts and ball cap, frequently setting off without sunscreen or water, just his “bins.” John has taken a special shine to the rephotography work and history, clearly thinking about his own museum as a historical as well as scientific institution. The last couple of days he has given himself over to that task, which has buoyed him.

James grew up in Rochester, NY, his father a social worker and his mother a local librarian. James has two brothers, one is a percussionist who refurbishes and sells vintage drum sets, mostly to Japanese collectors. James went to college in Fairbanks, Alaska, and did his PhD at LSU, where he met John. John later rescued James from a terrible job as a collections manager in Montana (or Wyoming) when John was hired at Occidental. He needed his own collections manager and James was the ideal candidate. James’s field style as unfussy as John’s: he wears jeans and has taken to carrying along a tote bag for the few things he takes along, which we’ve taken to calling his “adventure tote.”

Each plays a unique role on the expedition. John is decision maker and rarely busies himself with logistics and details. He doesn’t carry a camera, instead walking with binoculars and little else. This he leaves to Whitney, the Moore Lab’s lab manager who handles the organizational details—travel, food, gear, etc. John teams frequently with Whitney, who has a practiced eye for birds and the patience to record them. A true “Ant,” she is always up earlier than the rest of us, and before breakfast always has something to share. James, Collections Manager, is building the collection, not through collecting this time but through iNaturalist, the digital equivalent, and which has become something of a passion of his. In addition to acting as lister alongside James, Devon, a recent graduate in Biology at Occidental, is the trip’s learner. If this were a novel, I might use Devon as my proxy: the character who discovers the world of science through trial and error. There’s quite an education in witnessing James drill Devon on the finer points of identification and methodology.

Don Roland and Aeda live permanently in San Vicente, a small town on the coast up near Ensenada. One of the vaqueros who accompanied us to La Grulla is their son, who studies agronomy in Mexicali.

In bed earlier than usual tonight, by 9:30 or so.