11 June, 5:45am, Valladares

We wake to a damp morning, made more so by the fog that’s settled overnight in the sandy wash where we’re camping. Devon has been up and recording with the parabola since very early. The fog burns off quickly, and by 8 the sun is bright and warm. We make coffee and joke about Devon’s “sluggard” pace, the last to break down his tent. He and James get into it over Devon’s claim to have seen and heard a Cassin’s Kingbird, a bird James insists did not inhabit these parts. Later James is made to eat his words: Devon has in fact produced the first sighting of this bird on the trip.

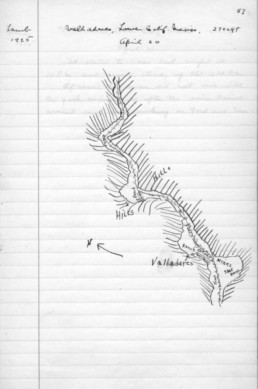

While James and Devon set off for a couple of hours to fill out the bird list, Whitney and I have a rephotography riddle to solve today: Lamb’s and Borell’s hand-drawn maps appear to match exactly this valley, but the Martorell house we camped near isn’t the house in #4800, “Old mining ditch above house,” as Rolando first expected. In fact there is no house where a house is indicated on the map–at least not any more–nor any remains of one.

To solve this, we think we might need a better view of the river valley, so we ascend the “red clay” hill (described thus in Lamb’s notes and on his hand-drawn map of the area) behind the arroyo where we camped. Borell’s notes to his map indicate “manzanita, creosote, and black oak,” but in reality there is redshank, chamise, and chaparral ash (whose bark turns black and whose leaves turn a bright yellow in dry seasons). Borell may have mistook the chaparral ash for some species of oak (though black oaks are mainly northern California): it’s a short scrubby shrub that might be taken for any number of chaparral shrubs or a scrub oak. Redshank does indeed have the hairy green leaves, deep red bark that sloughs, and small red berries that invoke manzanita. I suppose chamise might be mistaken for creosote.

So maybe Borell wasn’t much for plants. We look instead to the geography, but these river valleys are all starting to look the same, with their indistinct low chaparral hills and riverine bottoms. Lamb is little help: his map is more or less free of identifying details, but Borell’s is surprisingly detailed. From our vantage at the top of the hill, the landscape features match up pretty well with his: a (once-)cultivated field along an arroyo; a creek; and scrub hills in all the right places. Missing is an obvious contender for a “placer wash”–which presumably would have left tailings of the placer mine–and of course the ncessary houses. Maybe the tailings are obscured in the bush and the houses rotted away.

We log the location and snap some photos of the valley, more or less satisfied that we have reconciled the surrounding landscape with Borell’s map, and made some corrections too. We figure we must have camped roughly where the maps indicated that they camped.

On the way back, we snap a Northern Flicker, a Blue-Gray Gnatcatcher, Bell’s Sparrow, and a Northern Mockingbird. We also spy a Black-tailed Jackrabbit among the shrubs. In the arroyo, in the willows back toward camp, we see a Striated Queen and a number of vibrant, pretty Blues, like the Ceraunus Blue (Hemiargus ceraunus) and others in the genus Icaricia: Acmon or perhaps Lupine Blues–impossible to parse in the field and difficult even from photos.

We consult Rolando again about some of the other photos, of mines, an old Mexican cemetery, and “heavy brush habitat.” All of them again pretty nondescript. He suggests one more location, so we set off in the Ranger to another canyon, along another road that hasn’t been used for ages. It’s deeply rutted, washed out in places, obscured by vegetation, and we have trouble believing it to be a road at all. Rolando might simply be driving us straight up the rocky hillside.

11 June, Valladares Mines, 10:30am

Eventually we hit this “road’s” end and get a view of the foundation of an old house just in the right location for #4800: along a wide wash bisecting long valley. In the hills all around there is evidence of mining. Riddle solved. Everything here matches up perfectly: hand-drawn maps, original photograph, ruins of an old house. This morning’s adventures with Lamb’s and Borell’s maps turn out to have been some creative landscape fantasies on our part.

Since 1925, the arroyo has reclaimed the cultivated field and the house has been reduced to its brick foundation. The mining road cuts are still clearly visible. The old house was once a two-story homestead with white-washed walls, but now it’s a foundation of bare clay brick and stone. Sometime in the intervening 92 years, it was repurposed for a cattle corral, threaded with the characteristic barbed-wire-and-stick fencing over what must have once been the front door of the house.

Toward the bottom of the arroyo are the concrete remains of other structures—some tall pylons and a kind of reservoir fed by concrete channel–that must have belonged to the original miner’s community.

While I bushwhack into the canyon through the grabby chaparral to get a look at these remains, James and Whitney go after a Blue-Gray Gnatcatcher—a rare bird here–and one of Whit’s lifers, the Gray Vireo. These have an interesting distribution, she says: Some disjunct breeding populations throughout the southwestern US getting into parts of Mexico, one in Baja and another south of Texas. They do some wintering in Northwest Mexico and parts of Southern Baja.

Devon has hung back in the truck, dozing. He’s taken some Benadryl to ease a queasy stomach on the rolling ride, and it has put him out for the better part of the day. The rest of us spend the next hour reveling in the abundance of invertebrates in the wash. Hundreds of Polyommatini, the Blues, swirl and chase and woo one another, rising in tight circles from the arroyo scrub plants. Others, too: Gray Hairstreaks (Strymon melinus); a species of Metalmark (Apodemia); Common Buckeyes (Junonia coenia); Mournful Duskywings (Erynnis); and checkered skippers. And stranger ones we’ve never seen before: robber flies; a bright green metallic wasp; an orange bee fly; a large spider, the Silver Argiope, posed x-like on web strung across two paddles of a tuna cactus. We are briefly lost in this invertebrate paradise. At one point, both James and Whit are crouched down on the sand, their massive cameras trained on the smallest critters, mere millimeters from their quarries.

Back on the hillside, we find Roland napping beneath a juniper tree on the brown grassy hill. He tells us this spot is the “Mexican cemetery” in Borell’s photo (#4801). I wonder if the sacred datura (Datura wrightii) that dots this hill is a vestige of the digging of graves over the years. It’s a disturbance-loving plant and frequently follows human development. Historically associated with Indian village sites (Anderson 161), it’s one the few plants that the indigenous people may even have transported and cultivated because of its powerful (and dangerous) hallucinogenic properties and role in religious ceremony. None of the graves here are visible anymore: the datura, which doesn’t appear in the original photo, is the only remaining sign of consecration, but a fitting one.

Whitney and I quickly identify the mountain ridgeline from #4801 and set to work trying to get the angles right. It proves challenging and makes me think Borell was shooting with a wider-angle lens than I have. We can never quite get the ridge line in the distance to match up with the foreground, no matter what we try.

From this hilltop, we simply rotate 90° to get the re-shot of the “mines” (#4799), and another 90° for the “heavy brush” (#4798). This makes 4 photos from Valladares, all taken from the same hilltop—a bumper crop and a huge success for the trip out here.

It’s difficult to imagine that there was once a thriving mining community here, but “at one time,” wrote Lamb, Valladares “must have been a rich district for one can see where large sums of money have been spent.” (FN 4.14, 48). “The hills are full of mine tunnels dug by prospectors.” On the cultivated land along the arroyo—where we were just spotting butterflies—a rancher was growing peas, corn, and wheat to supply the miners. The road we traveled on was made for one of these gold camps, funneling adventurers and prospectors from San Diego looking to cash in on Baja’s mineral resources.

But even by 1925, Valladares consisted of just “one Mexican hut and a deserted mine” (FN 4.27, 66). The area had few visitors outside of the odd naturalist. When Lamb and Borell visited, they met only a solitary American trying his luck. They had arrived long after the end of a minor gold rush whose history might be traced to 1848 and the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which had ceded Mexican territories as part of the peace negotiations with the U.S. The Mexican government refused to cede Baja partly on the basis of its belief in its mineral resources (Taylor 464). According to surveyors, Baja contained gold, silver, copper, lead, since, iron, manganese, mica, salt, sulfur, and magnesite (Nelson). It had even been rumored that the early Jesuit missionaries discovered gold but had kept their findings secret (Taylor 467). Modest gold deposits were discovered in the mountains and coastal regions in the 1850s and then again in the 1870s. The end of the Alta California gold rush ignited a series of small-scale “booms” that drew prospectors from San Diego and attracted land development corporations that hoped to take advantage of the Mexican Colonization Act of 1883, which had opened up Mexico to settlement and development by foreign interests, like the company that had developed Colnett Colony where the Johnsons first settled.

But the history of mining in Lower California, like that of most other industrial interests here, is a history of decline. Mine after mine was abandoned in the late nineteenth century, leaving a trail of failed development ventures and bankruptcy. In general, the peninsula’s “desert character” (Nelson) proved too intractable, which must have been hugely frustrating given the region’s general accessibility to southern California. It was as if in crossing the border from California prospectors had entered a world that yielded itself to corporate interests only very reluctantly. As a result, the region was nearly as sparsely populated at the beginning of the twentieth century as it had been in the eighteenth century, when the Jesuits were among the few non-native inhabitants to the peninsula.

The largest mining operations were to the south, such as El Boleo, one of the largest copper mines in the world, developed by a French company, and El Triunfo, the largest silver mine in Baja, operated by an American company and located south of La Paz. El Boleo is actually still in operation to this day, but far more typical was El Triunfo, which, like most other operations in Baja, had experienced steady decline.

When Lamb and Borell visited here in 1925, the mines in the San Pedro Martir were little more than refuges for bats. In a single morning of trapping in Valladares, Borell visited fifteen abandoned mines and in three found bats in the family Vespertillionidae—the evening or vesper bats—including the smaller pipistrelles, the hoary bat, and the big-eared bat. One tunnel housed around 75 big-eared bats (possibly Corynorhinus townsendii), a species with long, flexible ears that lives in small colonies of usually under a hundred. When Borell approached these shy animals, they retreated to the back of the cave. The cave is deep, almost a hundred yards. When he finally reached them, they had “curled their ears on the side of their heads like a rams [sic] horns” (FN 260). This species of bat has declined overall partly due to human disturbance: when disturbed, whole colonies can abandon a roost. At the same time, though, according to researchers, human influence may have helped this species flourish along the West Coast: abandoned structures like these mines are ideal habitats for them (Arroyo-Cabrales, J. & Álvarez-Castañeda, S.T. 2017. Corynorhinus townsendii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T17598A21976681. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T17598A21976681.en. Downloaded on 5 May 2018).

The path from mining colony to bat habitat reveals something of the story of the creation of an environmental study site. Early inhabitants blazed the trails into the landscape. Industry deepened these so that they could reshaped the landscape, build structures on it and burrow into it. Industry left relics that created new habitats for study by scientist. Like big-eared bats, scientists found news uses for old industry, mining the landscape again for data, in the form of field notes, bird lists, maps, and photos. We’ve followed this data like a trail of breadcrumbs. Re-locating, re-surveying, re-shooting here isn’t simply a project of documenting a landscape; it’s also a process of re-inscribing the site, deepening its interest over time with new data–but also with new technologies: satellite waypoints and iNaturalist, for example. Every map, every new survey, adds a layer of data whose accumulation creates an archive to be explored, an ecological baseline to measure and re-measure.

I wonder how much a site like this becomes significant (that is, interesting to science) simply because we visit it. Valladares, like the other places we’ve visited, isn’t only a waypoint: it’s plot point in the story we tell about this landscape, a story that includes characters and conflicts and contexts. We’re not just passively documenting the landscape; we’re making it.

I regret we don’t take the time to walk more around the area to investigate the actual mines, perhaps see one of these ram-eared bats. But as this might have taken us some extra hours, we abandon it in hopes of getting back to Meling Ranch before dark.

11 June, 2pm, Valladares to Meling Ranch

We depart Valladares around 2pm and “drive” (or rather bounce) back to Meling Ranch after taking a group photo in front of the “Heavy brush habitat” (#4798). The truck ride feels less like taking a beating, probably on account of the mostly down-slope ride and because we more or less knew what to expect on the way—and we had more faith in both truck and driver. Whitney takes care to arrange our packs in a way to cushion the blows. And we also wear masks this time around, like road warriors fleeing some dusty, gasoline future.

The plan is to leave the Ranch for Punta Colonet, by the ocean, for two nights. But we learn I’ve made a mistake with our AirBnB and we have to ask Christian for another two nights at Meling Ranch and he obliges. We’re actually glad to stay here again: After the long couple of days, we are in no condition to drive back down to the coast anyway. We enjoy a cerveza with Rolando and another dinner at the lodge, this time without Christian. We won’t eat with him again on this trip and wonder if his absence has something to do with the payment problems the day before. We spend the evening getting cleaned up and working the bird list, iNaturalist, and field notes.